Part 2: Why does Culture Hacking Matter?¶

Failure in this system is like a cliff in the dark, a precipice at night that we can’t see until it is too late and we are about to tumble over it. We’re afraid of it, waiting for us out there in the darkness, and all we know is that we never want to get too close in our wanderings.

Hi and welcome to the second part on this series about culture hacking! You might have missed the first part, so if you want to recap, or you’re new around here I’d recommend checking out this first:

In the last post, I explained the origin of culture hacking (system thinking) and discussed how culture is the software of the mind, wether it be at a people level or organisation level. In this short post, I will try and make the case of why culture hacking isn’t just a gimmick used by start-ups to increase share prices in ping-pong tables.

I’ll be honest, I’ve re-written this post more than once, I think right now I’m up to the fourth time, and it doesn’t look like the post I started with, although in this, I’ve summed up the two key reasons I think culture hacking matters:

If you’re not hacking the organisation’s culture, there is a high likelihood someone else is, and chances are they don’t have your interests at heart.

By continuously hacking, and improving the culture of the company, you can increase resilience to external influence.

Security Culture¶

Now when I say culture hacking – I do mean security culture specifically, but you’ll probably find a lot of the techniques and issues discussed in these posts map well to other areas in tech, and even outside of it.

If you talk to me about anything security-related, I will bring it back to culture – when I did pen testing, I always tried to speak with empathy. I will also be the first to admit some days after seeing the nth + 1 web app with the same problem. I may have had a grumble-grumble. But the reality is being a security person is hard.

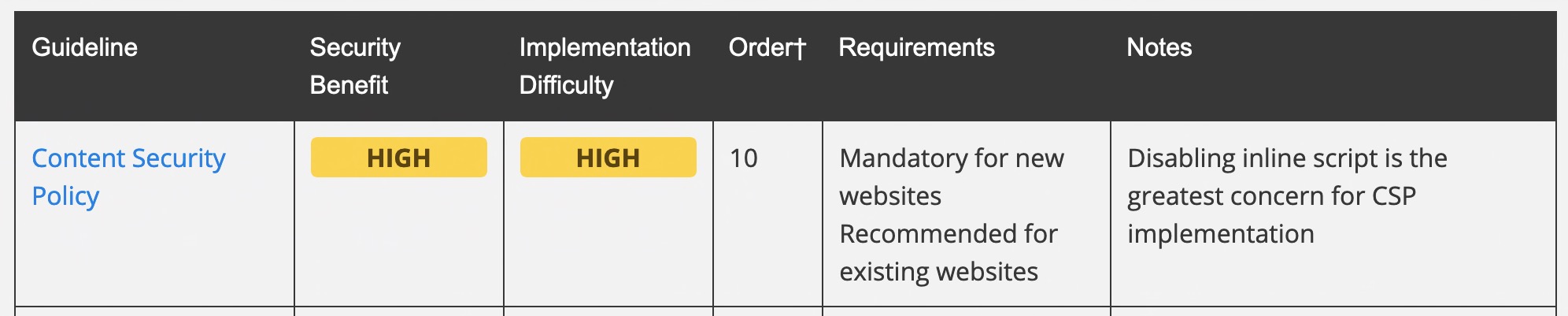

I still remember when I was still fresh, I wanted to see some movement on a ticket we had, had open for a while to implement a Content Security Policy – easy enough, right?

Anyway, at the time we were using one of those flashy frameworks that allowed you to make a web application and package it as an app, so it was even better that I didn’t have to come up with more than one variation.

I started my research, cataloguing the assets in use so I could add them to the allow list, except… a few required wildcards… Enter rabbit warren one… it turns out, that no we wouldn’t change those. Okay, well that’s okay… so off I go, and then I noticed that we had inline scripts and functions that needed unsafe-eval… and the story goes on.

This “simple” ticket scarred me so much I almost did a talk on it.

🌞 Even on a Good Day¶

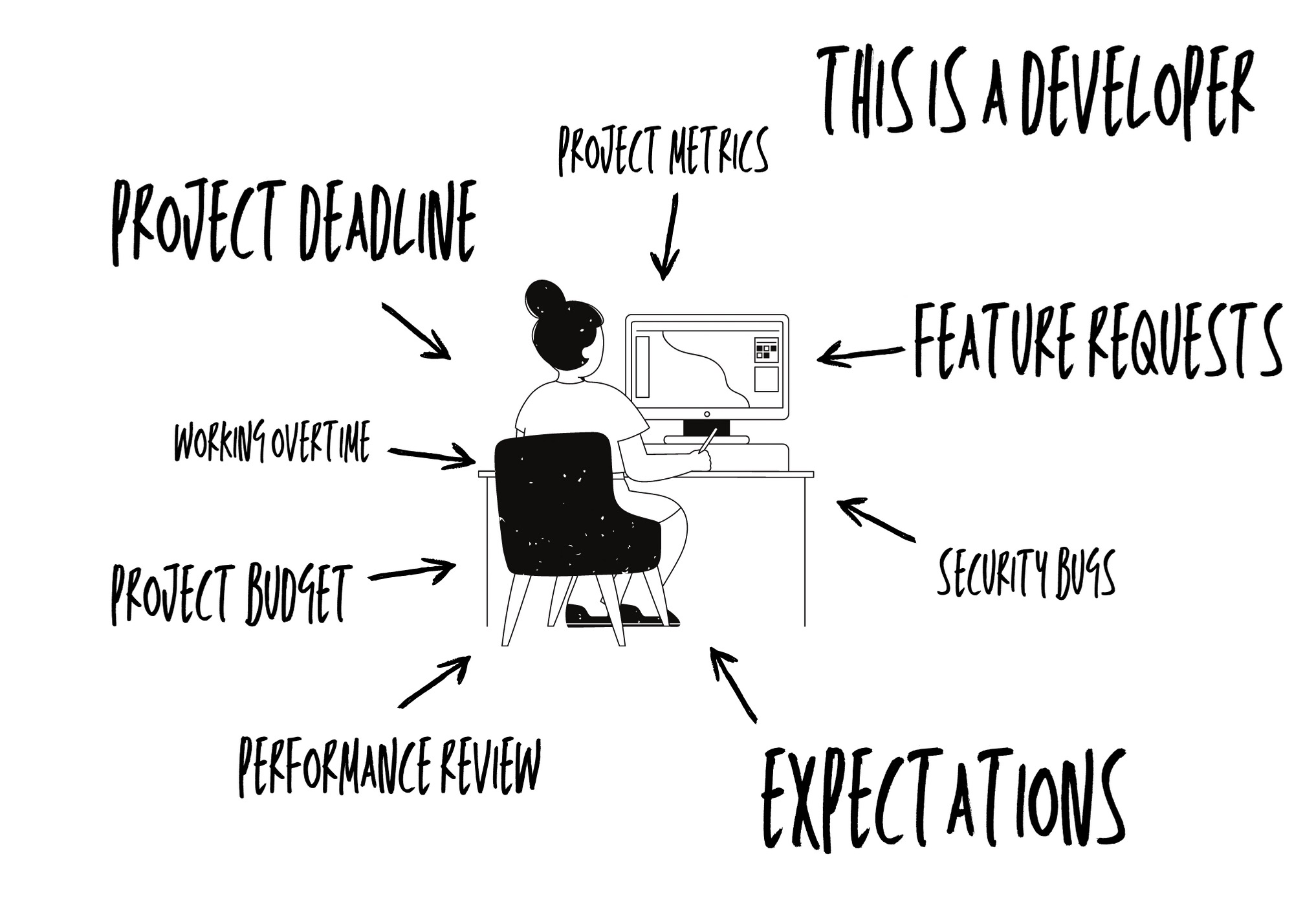

What’s your point Bec? Well, my point is, even on a good day where you don’t have other factors pressing in on you, security is challenging. But if we take the example of the developer, we can identify various other issues that may result in an inadequate security outcome:

With all of these external pressures imposing, which do you prioritise? Well, that depends on what the organisation demonstrate their values to be. If a developer has seen or heard of other people get reprimanded for prioritising x over y, chances are developers won’t make that decision for fear of reprimand.

On the flip side, co-workers and direct reports will see our developers decisions and emulate them.

🕵🏻 If you’re not hacking the company culture, who is?¶

Three sprints have passed and each time security has been put on the back burner to feature requests and project deadlines. Each time there is a risk of introducing more security bugs. Each sprint we move closer to the mandatory penetration test. As many security researchers and penetration testers may know when you issue that 30 finding report, that’s when it gets bad.

But of course, there is no right or wrong answer about what the priorities should be. Instead what we should be doing is looking for small areas of exploitation, or areas we can hack that we can use to ensure that the person in our example feels like they can make the right decisions at the right time.

Depending on the business and outcomes they seek to achieve this might be:

Having the DevSec, Dev or Sec teamwork on some security-focused pipeline improvements, so security is always part of the cycle.

Management can consider adding additional time to the project to meet project/security objectives and ensure developers aren’t working excessive overtime.

One on ones can be used to ensure that developers have adequate time to get feedback to inform what they should expect from a performance (360) review or manage their expectations of themselves.

Regular training and education in technical and living well skills to ensure developers can balance their work and personal lives.

Managers understanding work boundries and not imposing on them even when deadlines aren’t being met – instead working with leadership or project managers to push out delivery timelines.

Work to identify, install and configure guardrails, so developers and infrastructure teams don’t need to spend as much time doing work or reviewing concepts that could be automated.

Each of these recommendations can be further broken down into a smaller “culture hacks” that would release some of the pressure a developer faces when faced with conflicting priorities.

By continuing to make these small changes that improve people’s opinions on security culture and general wellbeing at your organisation, you’re also helping to make your culture more resilient to external influence. People can act as the cultural anti-bodies that feel safe calling out behaviour that doesn’t align with company culture and values.

Of course, keep in mind that in the same way, positive change can make a business more resilient to negative change. The inverse is also true.

🙌🏻 Summary¶

Ask yourself, if you’re not hacking the company culture, who is?

Security isn’t just a technical challenge; there is a significant portion that is a human/societal challenge – and these parts are a lot harder to solve. For every “bad” security decision you observe there is a human related reason.

Culture can be a significant indicator of how well a security program will work in an organisation.

By continuing to improve company culture, you can make your company resilient to change.